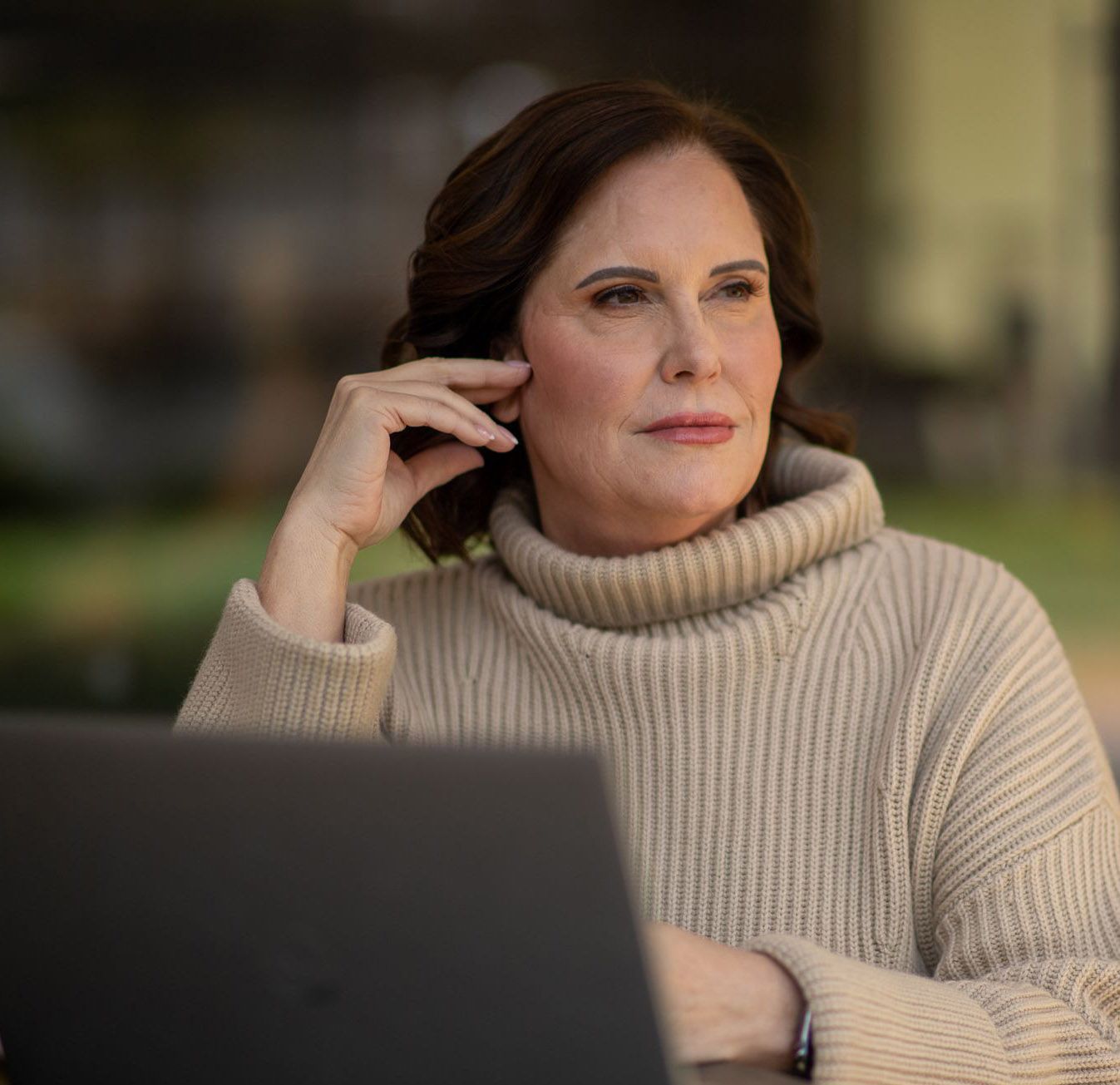

About Sheila

It required becoming a private investigator, overcoming dyslexia, and breaking through an unhelpful Dallas police department, but the persistence of Sheila Wysocki led to solving the 26-year-old murder of her friend and former college roommate, Angie Samota. Wysocki is now one of the most sought-after cold case private investigators.

Wysocki first met Samota when the two were freshmen roommates at Southern Methodist University. The two formed a close friendship, that continued even when Samota decided to move off-campus.

However, one night in 1984 changed the course of Wysocki’s life forever, when a stranger knocked on Samota’s apartment door in the early morning hours. “He said he needed to use the phone and the restroom, and because she was kind, she let him in,” says Wysocki. Realizing that she had made a mistake, Samota called her boyfriend, but her attacker had already cased the home.

Angie Samota was raped, murdered and stabbed 18 times. The murder scene was so gruesome that investigators initially believed that Samota’s heart had been ripped out. The death of her friend proved to be a crushing blow, leading Wysocki to ultimately drop out of college. “It was so out of anything that I understood in my safe little world,” says Wysocki. “I just didn’t know that evil existed. The death was traumatic enough, but the manner in which she died was life-altering.”

Wysocki spent the next two years speaking with detectives and even regularly met with suspects in the case. Even when she tried to distance herself from the murder, the death of Samota continued to hang over her head. "When I'd be out at restaurants or parties, I would look at someone there and wonder if they had anything to do with it," says Wysocki.

The introduction of DNA evidence in O.J. Simpson’s murder trial in 1995 began to get Wysocki thinking about exploring the case once more. But when she eventually gave birth to her two children, their medical conditions left her powerless to do anything. Both of them suffered from environmental poisoning, which led to weekly trips to the hospital. When their conditions stabilized in 2004, she was able to consider exploring the murder once more.

It was a Bible study session that year that led to Wysocki seeing a vision of her fallen friend – a clear sign to continue moving forward in finding answers to the murder. “I was sitting on my bed and at the end of my bed, I saw her smiling and could see what she was wearing,” says Wysocki. “And as crazy as it sounds, I knew then that it was time.”

She contacted the homicide division at the Dallas Police Department, who informed her that no one had called about Samota’s murder in 20 years. For the next two years, she called for updates on hundreds of occasions but was given the run-around by the department. They had no interest in reopening the case. “I just couldn’t understand how hard it was to pull the file and pull the DNA, but obviously it was for them,” said Wysocki.

Wysocki eventually spoke with JD Skinner, head of the security company in her gated community, who said her best bet was to become a private investigator. Suffering from dyslexia, Wysocki had her then 13-year-old son read her the book with all the laws that she was required to learn.

With her P.I. badge in tow, she reached out to the Dallas police once more but found them to be just as unreceptive. “The credentials did nothing,” says Wysocki. It just let them know that I wasn’t going away and was going to become a bigger problem, unless they started working on the case.”

Wysocki felt the homicide department was patronizing her. At one point in the investigation, a former detective's statement proved to be her most upsetting in the search for answers. “He told me that some cases weren’t meant to be solved, this was one of them and that I needed to back off,” she recalled. “I can’t tell you how angry that made me.” The case was later selected to appear on an episode of Crime Stoppers, but after getting into a heated argument with a detective who asked whether or not Samota was “loose,” they ended up pulling it from the program. “They still blame the victim in situations like this and it makes me so mad, but I learned that I have to bite my tongue to get what I want, regardless of what my feelings are,” says Wysocki.

After four years and hundreds of phone calls, she finally got a call from a female detective who was assigned to “investigate” the case. Detectives eventually relented and agreed to reopen the case in 2008. When they tested the DNA, they found a perfect match for five-time convicted serial rapist Donald Bess. Bess was ultimately detained and sent to trial, where he was convicted of the murder and sentenced to death in 2010. It was the only cold case that received a death sentence that year. And with that, Wysocki promptly retired her P.I. license. “I had worked some other cases and helped friends out, but there was only one case I had gotten my license for and truly cared about,” says Wysocki.

But Wysocki continued to get signs that her calling was perhaps not done yet. When she spoke at seminars, people would send letters or come up afterward and confess their own experiences with rape, asking her to help find their perpetrators.

She finally gained closure in the death of Samota when she revisited the SMU campus for the first time since the murder when her oldest son chose to attend college there.

But while the mystery of Samota’s murder has drawn to a close, Wysocki says she has now made a lifelong commitment to solving and preventing similar incidents. “I feel like if I’m not supposed to be doing this, a barrier would go up,” says Wysocki. “That hasn’t happened yet.”

Since renewing her license, Wysocki has blazed a trail in the private investigative profession, establishing new and innovative methods to solve cold cases. She produces a podcast, and trains others in her breakthrough cold-case-solving methods.